SIT REP (Situation Report)

Rodger W Brownlee

Spring has sprung and with it the trees and flowers are blooming, and birds and critters are matching up to nest and create new life. Spring is a time for renewal after the dark days of winter.

As part of that renewal, Spring is also a time of glorious rain, especially here in Texas where we hardly ever get enough. But so far this year, we have been blessed with an abundance of the stuff which has topped off our ponds, lakes, and reservoirs. But there are instances in other times and places where too much has been not a blessing, but a curse.

If you’ve ever been a field soldier, you know what I mean; water in your boots, your uniform soaked, water in your mess kit, trying to keep your weapon dry, leaky pup tents, trying to stay dry sleeping on wet ground, and mud; that clinging sticky substance that puts you into slow motion and saps your strength as you battle against it.

Mud is the bane of all soldiers and all armies. As I was writing “A Soldier’s Story” for this issue, I touched on the instances where the Allied armies, in their race across Europe, conducted numerous river crossings, the Seine, the Marne, the Moselle - twice, the Saar, the Rohr, and the Rhine among others. Many of these crossings were difficult, but conducted during normal weather conditions, while many were conducted during times of Spring or Winter floods. The swollen, flooded rivers became additional obstacles and barriers that benefitted the enemy. Incessant, record rainfall, for instance, contributed to record flooding of the Moselle River during the first crossing. “Water was everywhere, the approaches to the crossing sites were flooded”, and then there was the MUD. Just getting to the crossing site itself was often a major operation, often involving “trains” of wheeled vehicles linked together with cable and rope, and towed by a tank. It beggars the imagination thinking of what it was like for the poor infantryman often having to negotiate the knee-deep goo. Fighting the Germans and the elements alike, taxed the strongest of men, and stretched the resources of the armies to the limit.

Weather is always a consideration when planning any operation, and one of the more fickle aspects, often changing in a matter of hours or minutes, and changing the dynamics of the event.

Recently our own Bill Leaf got a taste after setting up a Museum display for the throngs of spectators attending the Air Show at nearby Naval Air Station-Joint Reserve Base. A storm front packing 40 mph wind gusts arrived, and Bill’s display and tentage was on the verge of being blown away, forcing him to scramble to wrap things up prematurely, but saving the day.

Mobile displays are an important, integral part of MMFW’s mission, providing museum quality displays as a learning experience for schools, special events, and other celebratory occasions. More recently MMFW provided displays for “Hops and Props”, a fundraising event for The Fort Worth Air Museum, and plans are in the works for an extensive display of the Vietnam War in conjunction with other local museums.

SIT REP CONT.

Further down the road, MMFW will be welcoming visitors attending the 90th Infantry Division Association Reunion to be held at the Sheraton Downtown Hotel in Fort Worth, on October 25-26, 2024. MMFW Founder and Curator Tyler Alberts, is also the Historian for the 90th ID Association, and so this will be an important opportunity for the MMFW to showcase not only the Museum in its entirety, but also the exhibits featuring the 90th from WW I to the present (some of these 90th ID exhibits provided the foundation for the museum when it was established). We understand that shuttles will be provided for reunion attendees from the hotel to the museum and back. We will have more information about the reunion on our website, www.militarymuseumfortworth.org as it becomes available.

In other news, restoration of our M3 Stuart tank and white half-track are proceeding at a snail’s- pace due to limited funding. We are still looking for sponsors to fund these restorations. If you know of or can think of any, please share your ideas with us. On the positive side, we have made a down payment on a replacement engine, and have received our recently purchased wiring harness for the half-track.

One of our goals this year, is to reach out and connect with more groups and organizations containing significant numbers of veterans and retirees. These demographics are a bedrock of support and continuity, not to mention our best source of advertising; can’t do much better than “word-of-mouth”. Our immediate goal is to reach out and to set this train in motion.

As ever, we are always in need of donors and volunteers. Keep this front-of-mind, and contact us if you have any ideas or suggestions.

Till then, enjoy the Spring rains, but watch out for the Mud.

Out Here.

| Tyler Alberts | Co-Founder/Executive Director |

| Rodger W Brownlee | President/Newsletter Editor |

| John Kalvelege | Vice-President Director |

| Karen Garrison | Media and Communications Director |

| Trace Chinworth | Director |

| John T. Furlow | Treasurer |

| Mike Zamulinski | Secretary/Outreach Director |

| Bill Leaf | Special Projects/Board Member |

| Ron Lane | Board Member |

| Stacey Sokulsky | Board Member |

| Dale Wagner | Board Member |

| James Warner | Board Member |

| VOLUNTEERS | |

| Randie Debnar | Volunteer |

| Colin Fish | Volunteer |

| Donna Kelly | Volunteer |

A Soldier's Story

Rodger W Brownlee

ONE OF THE “T. O. BOYS” - Part 1

ONE OF THE “T. O. BOYS” - Part 1

SGT EMSLEY C MEEK JR 90th Signal Company 90th Infantry Division – 1942/1945

Emsley Clete (EC) Meek Jr. was born in a half dugout, on a farm on the open prairie between Altus and Olustee, Oklahoma on 2 May 1922. He was the second of six children born to Alice Catherine (Martin), and Emsley C Meek Sr, a WW I veteran who served as a Private First Class in the 133 rd Field Artillery, 36 Infantry Division.

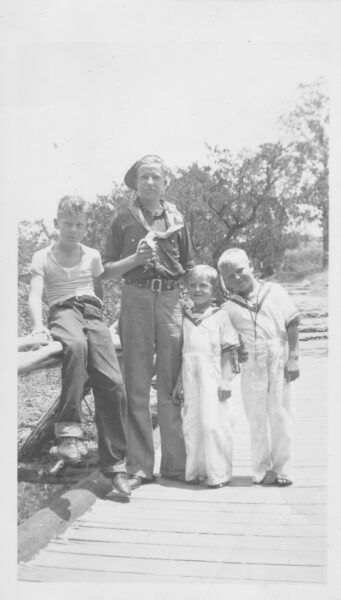

E.C. Meek Jr 1930 - L-R: Harold Martin, E.C. Meek Jr, Kenneth Meek, Johnny Martin held by Viola Meek, Marjorie Meek - Snomac, OK

Returning home from France at the end of the war, Emsley senior married Alice in 1919, and settled in rural Oklahoma to start his family. Times were austere for returning veterans, and having only a limited elementary education, Emsley senior hired on as a day laborer and farm hand. He often had to leave his wife and family on their own for days at a time as he traveled about in search of work. Nevertheless, by the time they had their third child, they had moved into a frame farm dwelling to house their growing family.

By the time E. C. (to avoid confusion, Emsley junior was simply called by his initials, and would be so known by for the rest of his life) reached his eighth birthday, double calamities had descended on the country; the “Great Depression” beginning in 1929, and the “Dust Bowl”  began its reign of terror throughout the mid-west in 1930. These two life-changing events would greatly add to the deprivations of a people already struggling to survive, but it would also toughen them with a resilience and resolve they would need for the trials ahead in the not-to-distant future.

began its reign of terror throughout the mid-west in 1930. These two life-changing events would greatly add to the deprivations of a people already struggling to survive, but it would also toughen them with a resilience and resolve they would need for the trials ahead in the not-to-distant future.

Unlike many of their fellow “Okies”, who pulled up stakes and migrated west, (as best depicted in John Steinbeck’s novel and the subsequent movie, “Grapes of Wrath”), the Meek family moved back to North Texas and settled among relatives in and around Grapevine, Texas and what is now Southlake Carrol.

By the end of the decade known as “the Dirty Thirties”, the “Dust Bowl” had run its course, the end of the “Great Depression” was in sight, and world events were taking center stage. In 1935 the Italians invaded Ethiopia, in 1937 the Japanese invaded Manchuria, and in 1939 Germany invaded Poland. These events previewed a conflagration that would soon envelop the entire world.

Meanwhile, the United States was rebounding from the depression and experiencing an economic boom, as defense industries hired in the tens of thousands in order to fulfill the country’s treaty obligations under “Lend-Lease”, and to live up to its role as the “Arsenal of Democracy”; providing much needed war material to its allies. For Americans deprived by the ravages of the “great depression”, tangible prosperity was finally becoming a reality.

The Meek family, following opportunity, moved to Odessa, Texas, where Emsley Sr. and E.C., who quit school after 10th grade to help the family, both took jobs as roughnecks in the burgeoning oil fields; where E.C. turned 19 in May of 1941.

This then was the state of affairs for the Meek family and millions of other Americans, when on Sunday, December 7, 1941, the Japanese carried out their sneak attack and bombed Pearl Harbor Hawaii. The United States immediately declared war on Japan; which was quickly followed by Adolph Hitler’s declaration of war on the U.S. Americans once more found themselves plunged into a world war, this time on multiple fronts. A world war that would impact and forever change their lives.

E.C. bided his time at first, but after his 20th birthday, reported to his draft board of record in Dallas, Texas, where he enlisted in the Army on 19 October, 1942.

Events moved quickly after that. By November 3rd, he had arrived at Camp Wolters, near Mineral Wells, Texas for induction and processing. His first letter home, written on a 1 cent postcard, simply read:

“Dear Dad, Bud, and Viola; I hope you are getting along as good as I am, I have plenty to eat and drink. This is my fourth night in camp, and I am making it better than I expected. We’re all mixed up pretty bad, big men little men old men and young men. Tell Jack if you ever see him again he had better increase his family another one or he’ll be in this mans army too. Love E. C.

P.S. Don’t write to me till I tell you to.”

By 17 November, 1942, E.C. had moved further west to Camp Barkeley near Abeline, Texas where he was assigned to the 90th Signal Company of the recently formed 90th Infantry Division; the “Tough Ombres”, or as E.C. preferred to call them, “the T.O. Boys”. (For the rest of his life, E.C. was very proud of the fact that he had been a part of the “T.O. Boys”, and bragged about the fact that the “T” and the “O” stood for Texas and Oklahoma; his home state and state of birth).

In his first letter home from Camp Barkeley, the day he arrived, he wrote; “Dear Dad, Vi, Bud, an Frisky,” (the dog)“……the boys sure are a swell that I’m with……I started school today……I don’t have anything (much) to say, but I think of you, I play the guitar and sing…… ”.

In his next letter, on 23 Nov., he writes; “Dear Vi, and Bud,……Yes the signal company is a good outfit, it has everything from radios down to pigeons ……most of the boys here are from the north……I have a pass to leave camp but I never use it……they say Abeline just runs over with officers and M.P.s and soldiers on Saturday, so I didn’t take the chance……I guess I was sure lucky to get here……the only one from Fort Worth to get in this outfit……”

After Basic training and Radio school, training intensified, and opportunities for overnight passes and letter writing became more infrequent; and as 1942 turned into 1943, new training challenges were on the horizon.

In early1943 the Division took part in maneuvers in Louisiana for approximately two months, and then returned to Camp Barkeley for additional training in village fighting, attack on fortified areas, close combat, and other subjects required to face an experienced, well-trained enemy.

By this time, there seemed to be no doubt that the “Tough Ombres” were destined to square off against the Germans rather than the Japanese. This seemed to be further confirmed, when in September, 1943 came the “call of the desert,” and the 90th packed up its belongings in order to engage in desert maneuvers in Arizona and California. Sand dust and heat, plus the 93rd Division were the opponents during the three-month period which ended in December. (1)

For a Texas boy used to the rigors of outdoor life and the west Texas heat, E.C. never mentioned the discomfort of the desert conditions, but often remarked that his main concerns in that environment were the rattlesnakes and 5-inch long, “child killer” scorpions, which had the nasty habit of cooling off during the day in the sleeping bags and boots of the soldiers. Not shaking these items out before use could lead to a nasty surprise for the unwary G. I.

In December, the month that the desert maneuvers ended, their movement orders came, and on January 8th of 1944, the 90th detrained at Fort Dix, new Jersey, their pre-staging area for overseas shipment, followed by a move to Camp Kilmer where last-minute checks and preparations were made. (1)

A Soldier's Story Cont.

On March 22nd, the Division entrained for New York, and on the 23rd without delay, boarded their ships; E.C. and the rest of the Signal company aboard His Majesty’s Troopship the Dominion Monarch; without fanfare or ceremony, they sailed out of New York harbor. They arrived in Liverpool, England without incident, from whence they were transported by rail to their assigned billets; E.C. and his group near the city of Cardiff, Wales.

Additional intensive training was the order of the day throughout April and May. During this interval in England, E.C. would turn 22.

“Invasion fever” was running high, and the troops were tensed like a coiled spring, waiting for “the word”. On the other side of the English Channel, the Germans were confidently awaiting “der tag”, knowing the invasion could come at any day or hour.

E.C. always told of going ashore on “D-Day”, and so may have been a part of “Group A”, the advance elements of the 90th attached to the 4th Infantry Division. At any rate, he told of being loaded onto landing ships on the 4th for the planned invasion on the 5th, but due to the bad weather which delayed landing by one day, they were forced to ride out the storms on board the landing craft, resulting in practically everyone becoming sick by the time they eventually sailed for Normandy.

By the 8th of June, the entire division was ashore on Utah Beach and ready to commence operations; warning orders were received that evening. “The 90th will attack……” The Signal Company was immediately and heavily engaged with laying wire to the scattered Regimental HQs. As a lineman, Pvt. Meek was right in the middle of the action. Later, he would often refer to the operations in Normandy as the more dangerous periods of his military service in the ETO. Being in such close proximity to the enemy, without any “lines” of demarcation, and not knowing exactly where they were, added to the confusion of operating through the maze of hedgerows. This fog of war in the early days of the campaign made for many a sleepless and dangerous night, often with tragic results. Many of the green, untested soldiers were “trigger happy”, which led to the unfortunate death of E.C.’s squad leader, Sgt. Back, who was shot and killed by his own men as he walked the perimeter near a Regimental HQ on the evening of June 10th.

The opposing Germans were a tenacious and treacherous foe. E.C. told of how they would infiltrate the American lines during the night, killing G.I.’s in their foxholes, then waiting for their reliefs to arrive, to ambush and kill them as well. They would cut the commo wire the Americans had laid, and wait in ambush for a lineman to come out to repair it. In the telling of these stories, E. C. would refer to the Germans as “krauts”, and offered that they were “mean and sneaky bastards……”

In Normandy, E. C. had many close calls, more than at any other time during the war. In his own words:

“……by this time, I had a jeep with a trailer that carried all my spools of wire and all my other stuff. I was driving down this sunken road with hedgerows on each side that made it pretty dark in there. As I rounded a corner, there was a loud pop and a loud clang like someone had rung a bell on top of my head. My head hurt and I was seeing stars. I jumped from the jeep and took cover. Some G.I.s came along and I told them what happened. They took cover and then worked their way down the road. I heard a couple of shots, and those guys came back down the road carrying that sniper’s rifle. I was lucky that time”. E. C. had indeed been lucky; the sniper’s bullet had cut a gash through the top of his steel helmet and dug a furrow through his helmet liner, but he suffered not a scratch. His ears rang and his head ached for a day or so, but he continued his work and sought no medical aid. He brought that helmet home with him at the end of the war, but eventually it somehow got lost or was stolen.

On another similar occasion, he came upon a stretch of road where soldiers were taking cover in the ditches on both sides. They cautioned him that they had spotted a sniper in the treeline ahead and that he should take cover. After his previous experience, he didn’t have to be told twice, and he took cover alongside them. Presently, a handful of boisterous paratroopers came down the road, drinking calvados, and obviously already drunk. Without ever taking cover, just swaying in the middle of the road, they were told what was going on and pointed to a clump of bushes that held the purported sniper. At that point, the paratroopers conducted a drunken leapfrog movement down the road until they were out of sight. Suddenly, the soldiers taking cover heard bloodcurdling yells followed by an unending string of cursing and obscenities. When the paratroopers came back along the road, a couple of them were still cursing, surrounded by a pungent, malodorous smell, while their inebriated comrades laughed and catcalled, while at the same time were keeping their distance. The G.I.’s in the ditch had indeed spotted the glint from a sniper in his lair, but unbeknownst to them, had apparently been dead and putrefying for a few days. This only became apparent, however, after a couple of the drunken troopers decided they would sneak up on the sniper from behind, jump him, and kill him with their trench knives. The plan worked up to the point where when they jumped the German, he fell apart under their assault. The chagrined soldiers hiding in the ditch also had a laugh over the incident, but held a healthy respect, and their noses, for the bravado of paratroopers, drunk or sober. E.C. called them, “…….the craziest S.O.B.s I ever saw……”

Another encounter with a sniper evoked a story with a more humorous telling. Telephone poles in France consisted of a square, tapered, cast concrete pole, with alternating square holes on adjacent sides, as a means to climb it. You had to be somewhat of a contortionist, as you had to insert your feet into the holes at right angles to each other as you climbed. The linemen loved them at first, giving a nod to the cleverness of the French, and for not having to strap on their ungainly climbing spikes. Also, the majority of these poles had survived the various shellings and bombardments, and so were utilized by both sides when it came to stringing their communication wires. So one day while stringing wire, E.C. was at the top of one of these poles, both feet jammed into the climbing holes, and both hands full, when a sniper opened up, pinging rounds off the pole, sending chunks of concrete and ricochets flying. Looking for a quick exit, E.C. found his boots stuck in the holes and jerked convulsively trying to wrest them free. Finally wrenching them loose, he slid down the length of the pole and slammed into the ground below, where he lay assessing any damage and trying to regain his breath. Checking his condition, he found that miraculously, the sniper had missed his mark, several times; that his ankles felt a little sprained, the insides of his legs were pole-burned, and his body felt banged up and sore from the hard landing. His buddies would joke about his circus trick exit from the pole, and he eventually enjoyed the laugh along with them; thanking his lucky stars that the sniper was such a lousy shot, or was he? (perhaps he was having a bit of fun with the hapless American and had a good laugh as well).

The Germans were cunning and resourceful soldiers. Making use of snipers, mines, booby traps, and every trick in the book to their advantage to slow down, delay, and kill their enemies.

The German SS troopers were even more treacherous; utilizing ploys such as pretending to surrender and then shooting their captors from ambush when they approached, or pretending to be wounded and then knifing the medic who came to treat them. Another deadly trick was to stretch a thin “piano” wire across the roads and paths frequented by jeeps to lop off the heads of its occupants. To prevent revealing reflections, jeep drivers in the bocage would usually have their windshields folded down. The piano wire, stretched neck high and practically invisible, lopped off the heads of many unsuspecting jeep operators until the simple solution of welding or bolting a vertical piece of angle iron to the front bumper put an end to this danger. Booby-trapping the dead bodies, bayonetting or smashing in the heads of the wounded with rifle butts, setting fire to paratroopers stuck and hanging from trees, and executing captured American soldiers out of hand were common practices for SS troops. These were among the dangers and brutal acts that E. C. and other soldiers witnessed in the Normandy bridgehead.

Faced with the deadly devices and treachery of the enemy, the G.I.’s soon discarded their natural and inborn tendencies for compassion and American “fair play”. Their consciences were put on hold, and their senses were constantly alert for potential dangers and treachery that could lead to injury or death.

These thoughts were always uppermost in E.C.’s mind, and even more so on an intense day during the breakout after “Operation Cobra”. The Germans were retreating and enemy soldiers were surrendering in significant numbers. By this time, E.C. had been assigned, in addition to his driver, a soldier to ride shotgun. Due to the nature of their missions, wire crews were instructed to avoid any direct contact, and were only to engage the enemy when necessary. Nevertheless, the addition of a “body guard”, was extra insurance when working on the wires between the lines in “no man’s land”. On this particular day, the soldier riding shotgun was a young replacement from the rear echelon, but he seemed competent, and was armed with an impressive array of firepower, including a Browning Automatic Rifle. E.C.’s crew headed out on a mission and as they rolled down a narrow country lane, there came a shout from the side and a German soldier popped out from a thicket. Glancing at his “shotgun”, E.C. could see that the man was terrified and frozen with fear. Grabbing the weapon from the frightened solder, E.C. shot and killed the German, all happening in a matter of seconds. The adrenaline rush was still pumping as they cautiously walked over to inspect the dead German. They found an obviously very young soldier armed only with a walking stick. E.C was always struck by seeing dead Germans up close; “……they were almost always very young, and looked just like our boys…” Seeing this young German soldier he had just killed shook him to the core; he had never killed anyone. For the rest of his life, a thought living in the back of his mind haunted him; had he acted too hastily; was this young German soldier simply trying to surrender? At the time, however, he had to put these thoughts aside and continue his mission, and try to keep his men and himself alive for another day.

After the war, like most veterans, E.C. was often asked the insensitive question, had he ever killed anyone, and like most veterans, he would frown, hem and haw and mumble a standard answer something to the effect “…….no, I just shot in the direction of the enemy like everyone else; I don’t know if I hit anything……”. But in one instance over a few beers, without being asked or prompted, he related this story to his brother-in-law, Bud; that he had indeed in an instant of fear and confusion, killed someone up close and personal, and that it had haunted him ever since. - TO BE CONTINUED –

THE OLD GUARD BUNCH

Rodger Brownlee

The "Old Guard Bunch" is an informal gathering of military retirees and their significant others who meet from time to time (there is no specific schedule) at the Golden Corral Restaurant at the address below to enjoy a good meal, renew old friendships, rehash our military memories, and just laugh and have a good time.

If you would like to be notified of up-coming get-togethers, or have any questions, please call or email Bill Abernathy at 817-401-9237 or Bill.Abernathy@sbcglobal.net or Wanita Lovell at 817-992-4018 or lovellsfc@yahoo.com. If no one answers the phone, PLEASE LEAVE YOUR NAME AND NUMBER.

NORTH TEXAS OLD GUARD BUNCH

Meets at

THE GOLDEN CORRAL

3517 Alta Mere

Ft Worth TX (at Alta Mere and Camp Bowie)

817-377-1034

ALL SERVICES BRANCHES ARE WELCOME

(Remember, No Schedules, Membership or Dues, Just Good Fellowship)